Meet the US Artists of the 2023 Venice Biennale Architettura

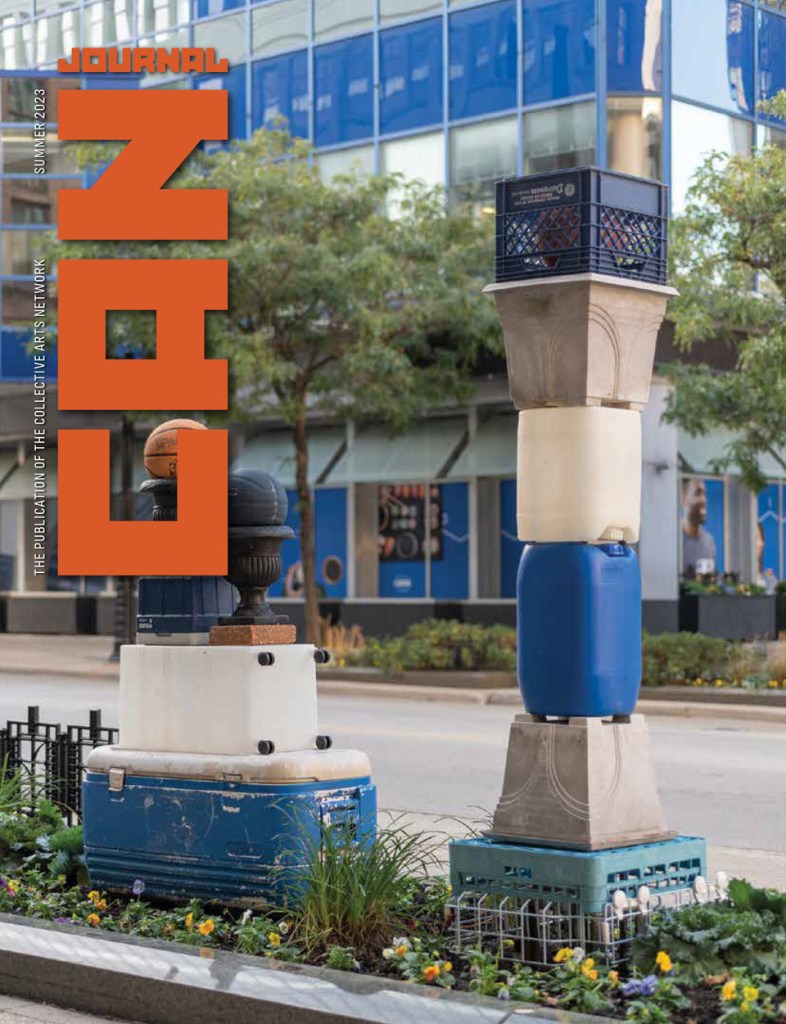

Executive Director and colleague, curator Lauren Leving to be part of Everlasting Plastics, the exhibition at the US Pavilion during the 2023 Venice Biennale Architettura. Pictured on the

cover are two of Yeager’s works, Cooler with Vessels and Dish Rack Tower, commissioned for Sculpture Milwaukee 2021. Photo by James Prinz.

As this issue of CAN goes to press, curators Tizziana Baldenebro of SPACES and Lauren Leving of moCa Cleveland were on the verge of departure for Italy, where they would oversee the installation of Everlasting Plastics, the exhibition they have built for the US Pavilion at the 2023 Venice Biennale Architettura. Their proposal, via Cleveland-based SPACES Gallery, was chosen by the State Department to represent the US this year—the first time ever for an Ohio institution. Baldenebro and Leving chose for the exhibition five artists, all from or with strong ties to the Midwest: Simon Anton (Detroit), Xavi L. Aguirre (Chicago/Detroit), Ang Li (Boston), Norman Teague (Chicago), and Lauren Yeager (Cleveland). According to a statement from SPACES, Everlasting Plastics “will present a series of works, ranging from sculptures to installations, which collectively invite visitors to reframe the overabundance of plastic detritus in our waterways, landfills, and streets as a rich resource.” CAN Journal spoke with each of the five artists to learn more about their practices, and what they were creating for the exhibition at the Venice Biennale. The exhibition is on view May 20 through November 26, 2023.

Simon Anton

Simon Anton is a Detroit-based artist primarily working with plastic. He graduated with his BS in architecture from the University of Michigan Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning, then went on to complete his MFA in 3D Design from the Cranbrook Academy of Art. While studying at the University of Michigan, Anton co-founded Students for the Environment, a program that focused on collecting plastic and recycling. He then began collaborating with others from the architecture school to tackle the technology of plastic-making. He has consistently worked with plastic since 2012 because it is embedded with contemporary issues, and he continues to learn more about the material and create new processes around it.

Environmentalism is one of Anton’s deep values, so he uses waste plastic in his art and design practice, transforming the material through knowledge and process. In Detroit, there is ample plastic industry, allowing him to source his materials from various industries including automotive waste. In 2022, he was awarded a Knight Arts Challenge grant for Transforming Trash, a project to teach local youth how to recycle plastic and turn it into public art. One of his passions is supporting younger designers through education and community, so this project aligned with the themes he enjoys.

Anton’s practice walks the spectrum between art and design, with works that are sculptural and decorative and others that can be functional and live in a home. His work for the Venice Biennale is concerned with architectural ornamentation, specifically looking at different points in architectural history. He is exploring new methods of working with plastic through a process of making metal sculptures and then grafting plastic onto those frameworks. “The Biennale environment provided a rich architectural pedestal to explore ornamentation at different points in architectural history while simultaneously talking about a very contemporary and future-affecting problem of plastic waste,” Anton said.

In addition to his artistic practice, Anton is co-founder of Got Grief House, an organization that supports Detroit area children, teens, and adults experiencing grief. He is also co-founder of Thing Thing, an experimental design group. Established in 2012, the organization designs processes to work intuitively with materials and methods usually reserved for industrial production—like plastic.

Website: thingthing.us/about-1/

Instagram: @pantasimon

Xavi L. Aguirre

Xavi L. Aguirre is an assistant professor of architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and an architectural designer. As a designer, they run stock-a-studio, an award-winning practice based in Chicago and Detroit. Their artistic practice consists of material assemblage that augments reality. Aguirre’s background is in set design, which later led them to architecture. Their installations are hybrids of sound, lighting, and moving images influenced by production design. “I think of architecture as a built environment,” Aguirre said.

Aguirre draws inspiration from the mundane, bringing awareness and attention to the expertise behind utilitarian objects. “We tend to ignore embedded intelligence,” they said. They highlight qualities that don’t often catch our attention, like the way music festival stages can be packed up into a truck—the reason being years of careful honing to perfect the design.

In connection with the Industrial Midwest, Aguirre uses Unistrut heavily in their practice. Unistrut is a channel often used to support heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems. It is a durable product, and the company is based in Ohio. Aguirre reappropriates this product, which is typically found in industrial settings, for more institutional and domestic spaces. They also paint Unistrut in bright colors that wouldn’t appear in a warehouse.

Aguirre’s work unearths new facts about plastics. They look at the materials used to create artificial environments meant to safeguard us against the elements. Often, the materials used to shield us from weather, water, or dust are the same materials at fault for the very environmental damage these shelters are meant to protect us from. The work for the Biennale will occupy two rooms of the pavilion. Aguirre constructed an immersive installation—“a complete world to bring the visitor into,” they said—that consists of four different tiny sets. Each set is reminiscent of what the artist considers an extreme environment and shows readiness for wear and tear. For example, one of the sets is a club, which must be prepared for partying, spills, and the like. There is also a video component. “The video is moody. It paints a picture of the end of the world and doesn’t glorify the materials,” Aguirre said.

The work for the Biennale is in many ways the culmination of Aguirre’s past work, exploring their trajectory from set design to architecture. They describe their work as observing how materials, commodities, and products pass through culture and our economies. It is about more than the materials; it is about the consequences that they trigger. “Materials come with baggage,” Aguirre said.

Website: stockastudio.com

Instagram: @stock_a_studio

Ang Li

Ang Li is an architect and assistant professor at the School of Architecture at Northeastern University. She earned her BA in architecture from the University of Cambridge and a MArch from Princeton University. Li is based in Boston, Massachusetts, and her research and creative practice investigate the maintenance practices and material afterlives of the contemporary building industry.

Li mainly uses reclaimed and recycled materials that people are familiar with, such as plastic and conventional building materials. Her work is informed by her background in architecture and its intersection with art. She looks beyond the building and at the curation of materials over extended time periods. Li creates site-specific installations and considers inherited site conditions, discarded materials, and consumption practices. In architecture, designs are prototyped so that they can be easily reproduced; Li’s artistic process departs from this tradition and moves into the stories that materials can tell. She is interested in what the waste-processing industry reveals about our consumption practices and value systems.

Some of Li’s more recent work considers the role of petroleum-based products in the building industry. Plastic is a common building material used by the construction industry in insulation, sealants, and liners. However, these materials are often hidden from view. Li confronts the role that these materials play, not only in construction but in ideas about the climate. The focus of her work for the Biennale is EPS foam, which is often used by the construction industry. The material is 98% air, so it is lightweight, which makes it appealing when building faster and larger. The work for the Biennale will be a 33-foot wall installation that examines the role of plastic within geological environments.

Li used to practice architecture commercially but doesn’t design buildings in her current practice. Her work looks beyond the existing market where there is room for speculation. “Architecture is a process making the invisible visible,” Li said.

Website: angliprojects.com

Instagram: @aaangangang

Norman Teague

Norman Teague is a Chicago-based designer and assistant professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago. He graduated from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and his practice is focused on projects and pedagogy that address the systematic complexity of urbanism and the culture of communities.

Teague tends to work primarily with wood, which often leads to furniture, products, or visual arts. His products range from chairs to shelving to retail fixtures and tables. “The work has become a way for me to tell or mend stories that recognize the ties to my heritage. My relationship with wood and found objects informs my reappropriating objects that carry a narrative, or the love I have for forming wood to do something new,” Teague said. He occasionally works in slip-cast ceramics in small batches. The original forms for the slip-cast items come from wooden and found objects. “The organized and intentional obscurity of the final object and its fired finish in porcelain gives it new life,” he said.

Teague is inspired by architecture, modern or traditional, that speaks to thoughts of family, traditions, dependency, equity, monumentality, language, or labor. His current work stimulates personal thoughts that visualize ideas on public space and speak a language of Black joyous freedom.

His connection to the Rust Belt comes from growing up in Chicago and noticing the varying infrastructure that supported a labor market and kept numerous families employed. The southeast side’s rail lines run parallel to South Chicago and to the remnants of factories waiting to be reappropriated. Today, like many people who live in and around these structures, he speculates on how these shelters can become new vessels of life.

Currently, with the invitation from the Everlasting Plastics curatorial team to the Venice Biennale, Teague has begun to explore the possibilities of reworking plastics to become new objects that pay respect to traditional hand works. “From collecting the proper plastics to carefully heating and extruding multitudes of colorful transitions to configuring them into new objects that reflect techniques that reflect our diasporic mother hand, it is a learning experience,” Teague said. “The overarching connection is the value that comes from having room to explore, which ultimately means making room for mistakes, retooling, and moving forward with learned lessons and using time to develop in-depth responses.”

Website: normanteaguedesignstudios.com

Instagram: @normanteaguedesignstudios

Lauren Yeager

Lauren Yeager is a Cleveland-based visual artist who holds her BFA in sculpture from the Cleveland Institute of Art. She works with found objects, and as of the past several years, she has used collected materials mainly sourced from curbside trash. Yeager enjoys the process of curbside collecting for many reasons: it’s exciting and fun, and feels more community driven rather than aesthetically driven. “I need to have some sort of reason or logic behind material choices,” she said. Found objects help the work feel more accessible because people are already familiar with them outside of the context of fine art.

She sees evidence of Northeast Ohio’s plastic production in her finds, such as five-gallon buckets and Step Two and Little Tikes toys. “These are national products that happen to be rooted here,” she explains. “I see it as a portrait of America, rather than specifically Ohio.” Generally, she doesn’t limit her practice to plastic only—she is open to other materials she finds on curbs, like terracotta, concrete, or domestic objects. Her work tends to be predominantly plastic because households often throw it away. “The formal qualities of plastic work well in the sculptures I create through different casting processes,” she said. Another reason she has access to a lot of plastic through gathering materials from curbs is because Cleveland has a large trash-gathering culture, but most people are looking for scrap metal—there is not as much competition for plastic. Using found materials also challenges her to evolve her practice and find new ways to incorporate something new.

Yeager is most inspired by connecting the formal qualities of found objects with art history, elevating them to a higher aesthetic than they were intended for. She references classical Greek and Roman architecture and more mainstream twentieth-century art that can be found in public places.

For the Venice Biennale, Yeager is constructing all new sculptures that will be outdoors in the courtyard. These sculptures will be placed upon gravel beds so that people can approach them more closely and wander through. There will be more than ten sculptures in total, composed of familiar objects that are common to us in the US, such as coolers and parts of children’s playsets. “I am trying to foresee how my background and practice can be placed in the new context of the Venice Architecture Biennial,” she said. “I am thinking about architectural history and how the objects and sculptures connect to it. The works will be responsive to the building and the courtyard. Scale was also a big consideration; I began seeking and incorporating larger objects into my compositions to balance the scale of the exterior site.”

Website: laurenyeager.com

Instagram: @laurenyeager_studio

You must be logged in to post a comment.