Elephants and Winnebagos: Eric Rippert takes memories down a new road

Eric Rippert’s darkling, toys-in-a-landscape photographs have for several years commented on innocence and alienation, and he has drawn some attention for those. Most visibly, two were printed large — highway scale –and installed on the West 14th Street underpass in Tremont, as part of the Cleveland Innerbelt Project Mural Art Program. In 2014 the Progressive Insurance collection – always a barometer of collectability — purchased a portfolio of 24 of Rippert’s silver gelatin prints. The Cleveland Museum of Art, which is an active collector of works on paper and photography by the region’s artists, also owns his work, as does Bidwell Projects. But Rippert is currently making different sorts of pictures. He’s gone down a road closer to collage, or print-making.

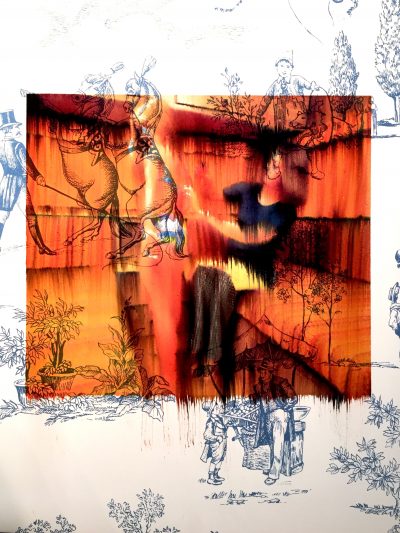

For these works Rippert sometimes re-shoots vintage 1950s and 1960s family photos superimposed on wallpaper patterns. Or he focuses his camera on pages from a vintage Winnebago sales brochure, or other advertizing idylls. Finally, he manipulates printing inks while they’re still fresh – brushes and wipes them, does subtle things that pull the work, like an ebb tide, toward memory. The resulting layered visions are veined with complex linear currents, sometimes illuminated by an overall flaring, toasted ambient glow. The memories they urge toward awareness flicker with forgotten sensations, pleasures and pains that still glow with the half-life of childhood intensity.

The wallpaper floating in the background of one series (in Rippert’s show at Maria Neil Art Project, opening September 2) are of a bucolic or exotic fantasy pattern, of a type common in the stairwells and bedrooms of tidy mid-twentieth century American homes. Sometimes an elephant wanders forward through the shallow pictorial layers, or a rose-entwined trellis bordering an antique garden obtrudes its fey scaffolding. Printed in red or blue outlines against an off-white ground, these figures have an hallucinatory transparency that dissolves perspective, drifting forward and carrying Rippert’s other images with them.

One shows a white RV moving in from the left, with a smaller model of a similar vehicle inset just in front of it, pulling farther across the narrative surface. We glimpse a family in the interior, a man at the wheel, a mother with children around her, wrapped in a blanket. (But is that a flower in her hair? Who are these people?) They’re in the cosy Winnebago, visible through its square windows – but the windows in the smaller van are pitch black. And veining this whole RV collage are the swooping outlines of a sylvan scene. A woman in voluminous skirts appears to be seated beneath a romantically twisted tree, playing with her children. Touches of color, a long blue rectangle of sky, and another of black – the road? – add to the dynamic of Rippert’s tale, which seems to be at least partly about travel and fantasy, about American vacation dreams of a certain period, with Disneyland or an incarnation of the Wild, set at the end of a blacktop rainbow.

Another picture shows a full color snapshot of the tight interior of an RV, where a young woman, seated on the bed, raises her arms, works on something. This is one of the pictures in which Rippert’s ink manipulations come into play, producing mini-cloudbursts, hanging mosses of color, blurring and washing the image like a long hot bath. Too hot, in this case. This image, “Sunburn, 1975”, has to do with Rippert’s painful recollection of an early, bad case of that affliction.

Rippert’s work here often teeters between hungry satisfaction and pure agony. In “Sunburn 1975” the images he uses are melting, dissolving into illegibility, but they feel remarkably intimate and in that sense focused, even magnified as the viewer is brought right up to the face of heat and pain, and the photographed, printed surface spills across the distance between minds. Many of the twenty-odd pieces in the show, all dating from 2016, are actually about interpersonal chasms, the incommensurate tendencies of love and gesture – the awkwardness and clown-suited phoniness of so much in life.

They read like documents from dreams. Wallpaper patterns whorl through half-remembered slices of life – watermarks grooved into the fibers of time. Or faces press together, hands clasp, Polaroid photos intersect with schematics of Winnebagos; everywhere abrupt changes in scale and intention, in plans, pose questions about who we are, where we are, what we want. Sometimes we’re anonymous figures in an old photograph, but always our postures, faces and feelings are echoed, backed up by archetypal templates. Actors and authors, also, appear in juxtaposition to family members in Rippert’s lost times; they rub shoulders with J.D.Salinger, Holden Caufield, or William Holden.

Meanwhile, around the corner on Waterloo in what they’re calling the Native Cleveland annex, Rippert’s blanket fort is on display. Like many people, the artist had one as a kid, but unlike most of us he still does. Although he’s using a real blanket, it’s decorated (thanks to contemporary blanket technology) with a photograph of the original,from his childhood. In that picture this oddly patterned, smallish fabric is draped between two tubular kitchen chairs. The real blanket echoes the image, forming an actual fort in the very small storefront gallery. The photographer’s succinct installation isn’t just a hall of mirrors or an artistic echo chamber; it might be viewed as a psychic time machine. Photography itself, of course, is like that. You could take the fort as a trope for the mind in general, for imagination and the membrane of disillusion which comes to envelop it.

Having settled in Cleveland after working for a number of years as a commercial photographer in New York City, Rippert has emerged over the past decade as a notable Midwestern artist. He holds his own with contemporary photographers elsewhere in the world. His new works follow long trajectories of imagery from remote childhood into the present, urgently contacting viewers with a hard-won sense of personal truth. No doubt even wider recognition awaits.

You must be logged in to post a comment.