Home is where the art is: Paula Izydorek and Debra Sue Solecki at CWAL

The current exhibition at the Cleveland West Art League, comprised of works by Paula Izydorek and Debra Sue Solecki, brings together the works of two artists who had not previously met, but who had converged on a single theme: home.

Izydorek explores “home” as a general, universal idea. This approach results in abstract, almost ethereal images. Many of the houses Izydorek paints are depicted from an upward-facing perspective, so that blue skies dominate the birch panels on which she paints. Sometimes, the houses are totally ungrounded, floating in blue or beige voids lined by black streaks and shapeless protozoan figures.

Architecturally, the houses are simple—two-story cubes or single-story rectangles with slanted roofs, square windows, and chimney stacks. For 21st century Americans, they are archetypes of what houses look like. However, every archetype is understood by an individual with her own idiosyncratic perspective. In “Cloudscape 10.15.1,” we see a two-story home painted in neon pink acrylics. Pale clouds luxuriate in a bright sky; one is filled with concentric ripples, like those a pebble makes when thrown into a lazy pond. An identical building appears in “Cloudscape 10.15.5,” but this time it is blue, just a few shades darker than the sky. The clouds are thicker, gloomier, and closer; another rippling cloud is low enough to partly block view of the house’s roof. It has the shape of a squinting, scrutinizing eye.

“Cloudscape 10.15.1” and “Cloudscape 10.15.5” unmistakably depict the same house, but through different perspectives. Maybe the viewpoints of two people with differing agendas are depicted; or maybe the two paintings represent outlooks of one person at two different points in her life. Nothing in the house’s structure changes painting-to-painting, but it is experienced in radically divergent ways. Everything is the same, and everything is different.

At least three distinct series or periods of Izydorek’s works are represented at CWAL. Not all are concerned with “home” understood as a residence and site of shared memories. But all three are about “home” in an extremely broad sense, perhaps better called “familiarity.” Works titled “Cloudscape” and “Home” have the most to do with houses and other sites of cohabitation and family-rearing. A trio of surreal nonfigurative works titled “(Self) Worth” meditate on the individual’s relation to themselves. While these compositions are abstract, they suggest landscapes. Black and pink holes suggest geyser pools, and snaking magenta stripes evoke lava flows. Lollipop-shaped “flowers” populate rolling blue hills. The images are beautiful, but alien, inexplicable. Just so, we can value ourselves without understanding ourselves.

In the final, most recent set of paintings, Izydorek turns attention to her own artistic practice. Throughout the “Symbiosis” series, she confidently deploys her technique in manners which are new, but recognizably her own. Acrylics and birch wood panels remain the primary materials in these works. Izydorek says that in previous works, she had let the grain of the wood influence how she put down paint. But in “Symbiosis,” she asserts herself over the birch’s texture, layering paint thickly or fortifying it with other materials. “Symbiosis 9.17.1” looks as smooth as an encaustic piece, except where rough, textured paint crackles off its surface. Faded pinks and green-grays swirl idly; the only motion suggested is that of black and blue bubble shapes, and grassy green veins. There is a welcoming stillness to the work.

Solecki contrasts Izydorek’s philosophical tone by digging deep into particularity. Her work is informed by the sense of place—firsthand knowledge of a region’s quirks and its collective, historic memory. Most of the places Solecki meditates on are in the Rust Belt, but she depicts other locales she has lived in or visited (Maryland, New York, Peru).

If Izydorek is a minimalist, Solecki is her maximalist opposite. One of her collages may consist of paint dripped over vintage National Geographic clippings, which are themselves superimposed over a map of the Great Lakes region. Coins, burlap, antique woodwork, tassels, and other found materials are also employed. Though from a distance these pieces can look like abstract mandalas, their meaning and content is only legible when they are examined up close, and at once component at a time.

“Growing up OH” is both a mental and geographic map of the Buckeye State. In the upper right (Northeast) corner, Cleveland is represented by a black-and-white portrait of a Cleveland Indians ballplayer, a panel from Golden Age Superman comics, and the Terminal Tower, lit by fireworks. In the center of the frame, Columbus is symbolized by the face of a clock tower at The Ohio State University. At the top, cavorting sailboats and a thrashing bass signify Lake Erie. Photos of snowy woods, silos, mills, college campuses, and neoclassical municipal buildings fill out the heartland.

“Growing up OH” is the sort of self-representation the postwar white middle class might have made of itself, had it approved of anything so avant-garde as found media collage. In Ohio’s southeast, a nuclear family (gray suited patriarch, coiffed mother, and girl in a neat red dress) sit on a couch, smiling at an unseen television. In the Northwest, a manly hand slips an engagement ring over a dainty finger with a manicured, painted nail. Norman Rockwell himself, avatar of wholesome Americana, makes an appearance alongside an ad promising “[Y]ou can be a successful artist!”

However, as in the actual midcentury U.S., not everything is swell. To the right of the TV-watching nuclear family, we see three American Indians in a historic illustration. One hunches over, troubled. Another looks to the left, as if seeing through time and witnessing the suburban future to be built upon native lands. Meanwhile, the ballplayer in Cleveland’s corner of the frame wears the original Chief Wahoo insignia, which bears an even longer hooked nose and wider grin than later versions of the caricature.

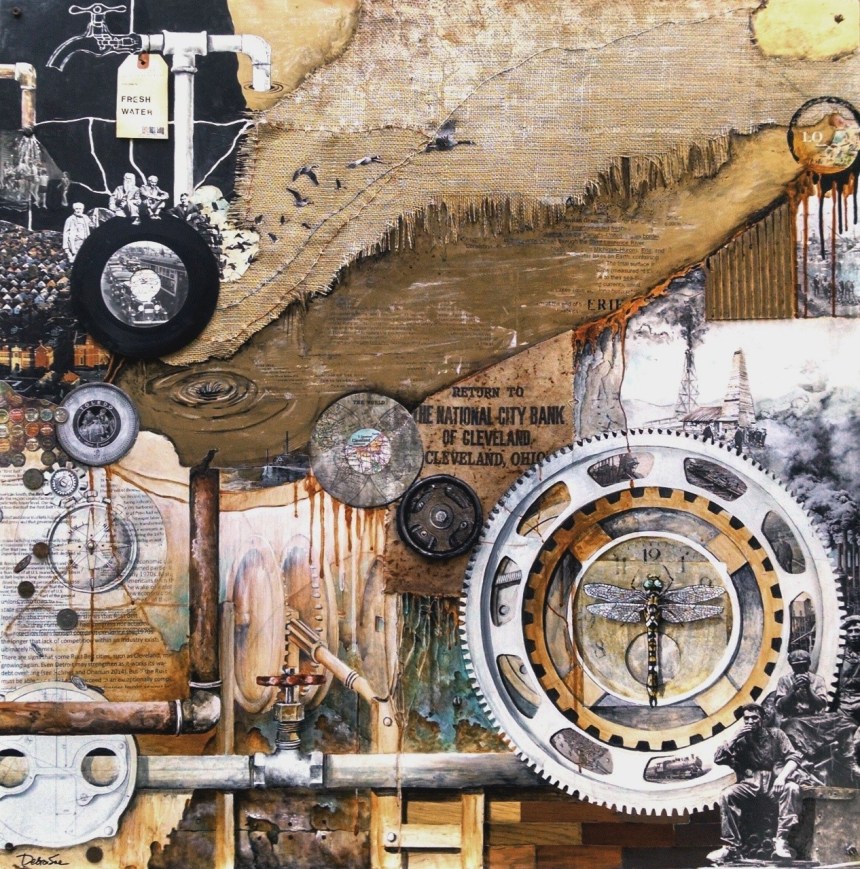

“Rust Belt Resurrection” is a historic mosaic of the Great Lakes region, with various decades of prosperity and struggle alluded to. The sepia surface of Lake Erie lies across the collage’s top half, indicating Pennsylvania to the east, Ohio to the south, Canada to the North, and Michigan to the west. Pennsylvania’s petroleum-flush past (and, possibly, its fracking-enriched present) are referenced with a drawing of an oil well, and photos of workmen enjoying a lunch break beneath spewing smokestacks. A dragonfly, gold-shelled and green-eyed, is enclosed in the spoke of an industrial gear. It sits unnaturally still, like a pinned specimen or illustration in an etymology textbook. The insect is likely a concrete icon of the abstracted “environment” degraded by fossil fuel use.

Pipes crisscross the face of “Rust Belt Resurrection.” One spigot, located in the “Michigan” quadrant, is combined with a photograph of a spewing fountain, under which skinny children play. Solecki said that this image is meant to invoke the ongoing water crisis in Flint. It not only invokes the scandal, but comments on it—Flint’s thirsty children are predominantly black, but the kids splashing carefree under bountiful water are white.

Not all of Solecki’s social commentary is so heavy. “Downtown for Dinner” is a gentle ribbing of suburbanites who treat “the city” as an inaccessible, exotic locale. Cleveland is depicted by such wonders as charging Browns players, the neon marquee of the Beachland Ballroom, youths diving into the open horizon of the lake, and an audience of theatergoers in 3D glasses. Solecki herself currently resides in Westlake, and that community’s name is paired with a sketch of a bird’s nest. “The nest,” symbolically, is where children are raised, and where parents retire to after those children are grown. It is, like the suburbs, a place of safety. But the most delicious visual metaphor for the ‘burbs here has to be a pink-orange circle in which are encapsulated the Virgin Mary, painted with a gilded halo, and a plastic lawn flamingo. The suburbs, we’re taught, are where the sacred lives side-by-side with kitsch.

But there’s nothing chintzy in Solecki’s wry social commentary, or Izydorek’s meditations on the strangeness of the things closest to us. The radically different approaches the two artists bring to both their craft and the subject matter makes for a highly stimulating show.

Solecki and Izydorek’s exhibition runs through February 16 at CWAL’s gallery in 78th Street Studios. The gallery is located at 1305 West 80th Street, Suite 110, and is open by appointment. A closing reception will be held during the Third Friday open house on February 16, from 6 to 10 p.m. To contact the gallery, email cwartleague@gmail.com, or go to CWAL’s website.

You must be logged in to post a comment.